Dec 29, 2025

An Elixir program consist of a large number of lightweight, concurrent processes communicating with each other via asynchronous messages. A process receives and handles incoming messages, transforming its internal state in a functional way. Inside a process, all code is sequential. The VM running Elixir, BEAM, normally utilizes all cores of a modern CPU and schedules processes for execution. By running many concurrent processes you can maximize the performance of current hardware.

What if we want to use more than one machine? Distributed Elixir refers to the capability of Elixir applications to run across multiple nodes within a cluster, allowing for improved scalability and fault tolerance. This is a complex subject, but we can explore the basics without installing any dependencies.

You create a distributed cluster, on the same machine or on machines on the same network,

by starting one or more nodes, giving each node a name, making sure they share the same secret,

and then connecting those nodes.

Let's begin and start our first node, foo,

using functions from the Node module.

$ iex --sname foo --cookie COOKIE-0123456789

iex(foo@pathfinder)1> Node.self

:foo@pathfinder

iex(foo@pathfinder)2> Node.get_cookie

:"COOKIE-0123456789"

Now we start our second node, bar and connect it to the first node.

$ iex --sname bar --cookie COOKIE-0123456789

iex(bar@pathfinder)1> Node.connect :foo@pathfinder

true

iex(bar@pathfinder)2> Node.list

[:foo@pathfinder]

Both nodes now know each other. When either node dies, the connection disappears.

iex(foo@pathfinder)3> Node.list

[:bar@pathfinder]

What Distributed Elixir fundamentally offers is the ability to send asynchronous messages to processes living on other nodes. The great thing, the magic, is that this happens transparently. It looks exactly the same as sending a message to a local process.

OK, but how do we get started, exactly ? We need a way to refer to a remote process. For this we can use Erlang's global module. This is a distributed registry for processes. It is simple but powerful. It keeps local registries in sync with each other so that they share one global view, without a central storage point.

Let's use the Agent module an an example.

This is a process that holds a value that can be queried or updated.

On our foo node, we create an agent1 and give it a value.

Note how set the name through the global registry.

iex(foo@pathfinder)4> Agent.start(fn -> 42 end, name: {:global, :agent1})

{:ok, #PID<0.117.0>}

iex(foo@pathfinder)5> :global.registered_names

[:agent1]

The bar node has automatically sees the same global registry.

We can now refer to agent1, living remotely, and use it as if it were a local one.

iex(bar@pathfinder)3> :global.registered_names

[:agent1]

iex(bar@pathfinder)4> Agent.get({:global, :agent1}, fn x -> x end)

42

iex(bar@pathfinder)5> Agent.update({:global, :agent1}, fn x -> x + 1 end)

:ok

Any change that we make from bar is visible on foo, of course.

iex(foo@pathfinder)6> Agent.get({:global, :agent1}, fn x -> x end)

43

Please consider what is all happening here. The code of the Agent module knows nothing about distributed processes, as we will demonstrate later with our own code. Communication goes via the network, the message is serialized on one end and materialized on the other end. The message does not just contain data, it contains a function. We get a result from a remote call, from code that doesn't know it is no longer working locally.

The starting point of this magic lies in the nature of PIDs.

iex(foo@pathfinder)7> :global.whereis_name :agent1

#PID<0.117.0>

iex(bar@pathfinder)6> :global.whereis_name :agent1

#PID<13530.117.0>

The PID of agent1 is different on both nodes.

The first number is zero for local processes,

and some number referring to a node for remote processes,

while the second number remains the same.

When the VM needs to send a message, it uses this to do something different.

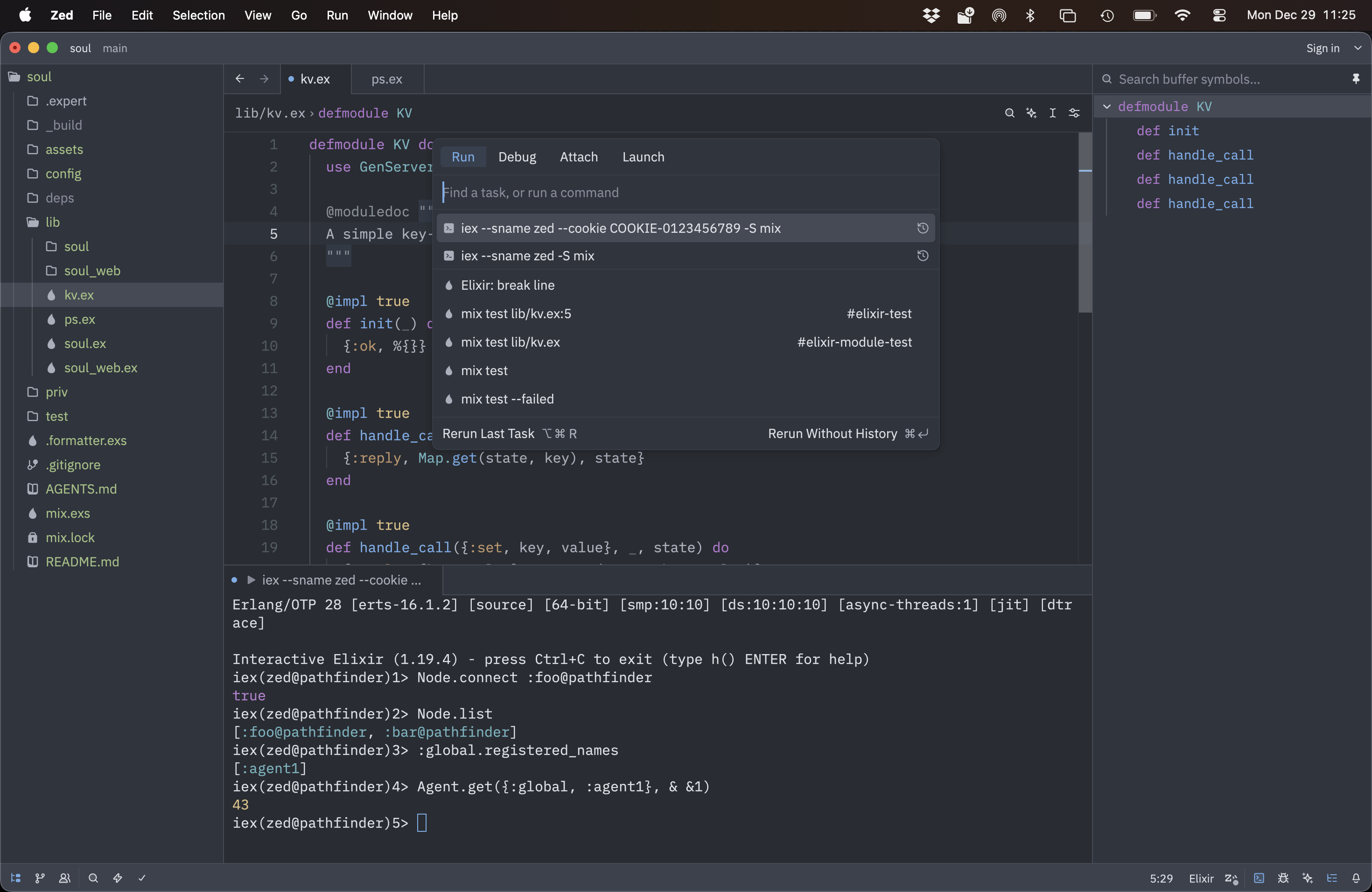

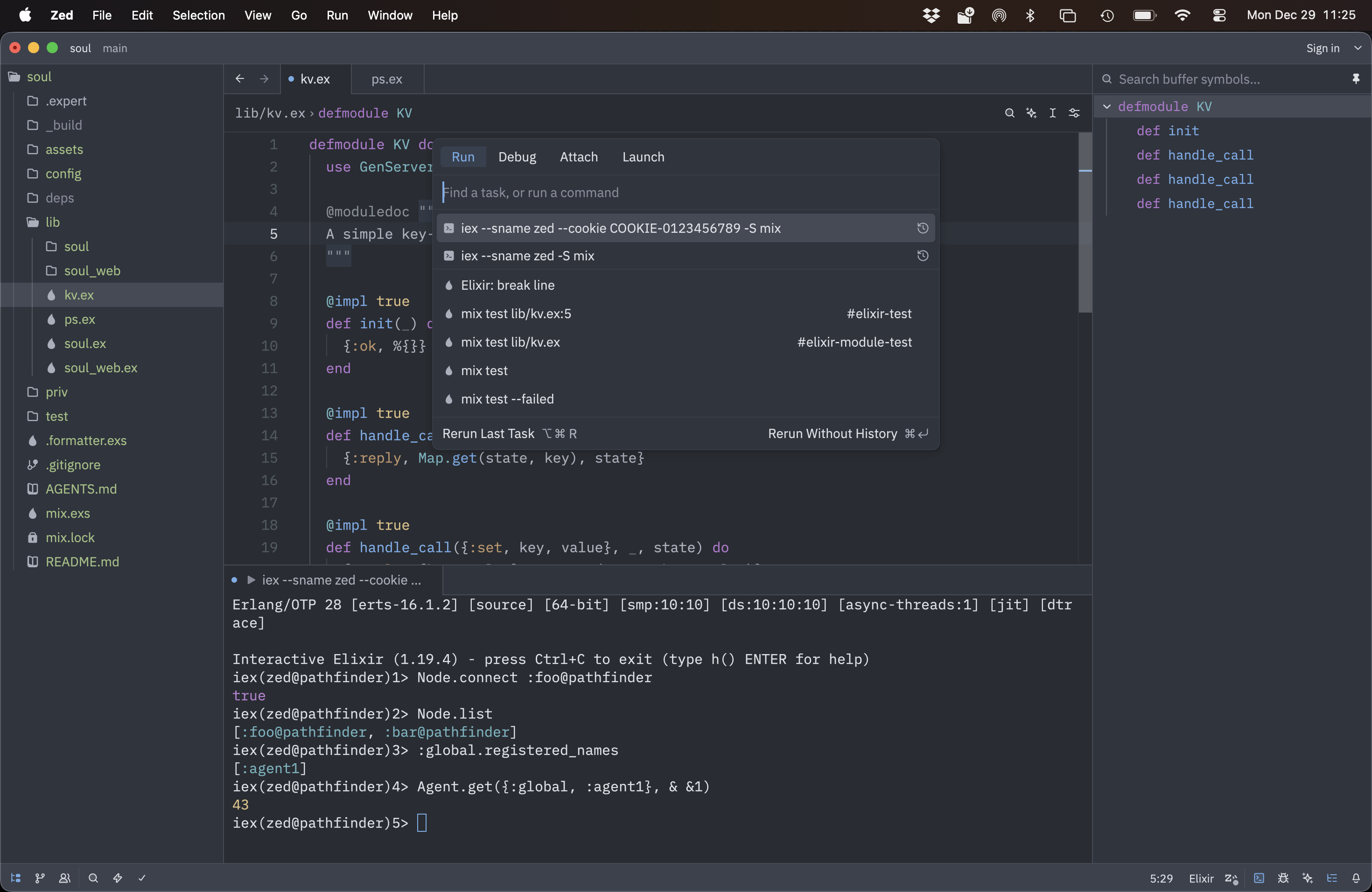

Let's write some code of our own to drive home the point that working with remote processes happens transparently. At the moment my favourite IDE for Elixir is Zed. Here we run another node inside Zed and add it to our existing cluster.

Here is a log of the interaction inside Zed, from the screenshot above.

$ iex --sname zed --cookie COOKIE-0123456789 -S mix

iex(zed@pathfinder)1> Node.connect :foo@pathfinder

true

iex(zed@pathfinder)2> Node.list

[:foo@pathfinder, :bar@pathfinder]

iex(zed@pathfinder)3> :global.registered_names

[:agent1]

iex(zed@pathfinder)4> Agent.get({:global, :agent1}, & &1)

43

Note how we connect to the cluster by referring to foo,

yet we immediately see bar as well.

Furthermore, the global registry is immediately available to us,

and we can use the existing agent1.

Let's try a super simple key value GenServer.

defmodule KV do

use GenServer

@moduledoc """

A simple key-value server.

"""

@impl true

def init(_) do

{:ok, %{}}

end

@impl true

def handle_call({:get, key}, _, state) do

{:reply, Map.get(state, key), state}

end

@impl true

def handle_call({:set, key, value}, _, state) do

{:reply, true, Map.put(state, key, value)}

end

@impl true

def handle_call(:keys, _, state) do

{:reply, Map.keys(state), state}

end

end

Again, using the different naming scheme is enough to publish our process to the cluster.

iex(zed@pathfinder)5> GenServer.start(KV, nil, name: {:global, :kv1})

{:ok, #PID<0.332.0>}

iex(zed@pathfinder)6> GenServer.call({:global, :kv1}, {:set, :foo, 123})

true

Now any node on the cluster can access kv1.

iex(foo@pathfinder)8> GenServer.call({:global, :kv1}, {:get, :foo})

123

Our three nodes are running on the same machine. Using another machine is just as easy.

sven@pathfinder ~ $ ssh enterprise

Last login: Tue Dec 23 14:46:45 2025 from 192.168.178.103

sven@enterprise ~ $ iex --sname mini --cookie COOKIE-0123456789

Erlang/OTP 28 [erts-16.1.2] [source] [64-bit] [smp:10:10] [ds:10:10:10] [async-threads:1] [jit] [dtrace]

Interactive Elixir (1.19.4) - press Ctrl+C to exit (type h() ENTER for help)

iex(mini@enterprise)1> Node.connect :foo@pathfinder

true

iex(mini@enterprise)2> Node.list

[:foo@pathfinder, :zed@pathfinder, :bar@pathfinder]

iex(mini@enterprise)3> GenServer.call({:global, :kv1}, {:get, :foo})

123

As you probably know, GenServer's call function uses asynchronous messages to give the impression that we have a RPC call with a synchroneous request and response. It refers to the caller process, which is remote from the standpoint of the server's implementation. When a message send transfers from one node to another, any PID's inside it are converted from local on the caller to remote for the callee.

To explore this inverse referencing, we can try to implement a simple PubSub GenServer. BTW, the Phoenix version is also cluster aware, we're doing this as an experiment. Here is the first version of the code.

defmodule PS do

use GenServer

@moduledoc """

A simple publish-subscribe server

"""

@impl true

def init(_) do

{:ok, %{}}

end

@impl true

def handle_call({:subscribe, topic}, {sender, _call}, state) do

new_state =

Map.update(state, topic, [sender], fn subscribers ->

if Enum.member?(subscribers, sender) do

subscribers

else

[sender | subscribers]

end

end)

{:reply, true, new_state}

end

@impl true

def handle_call({:unsubscribe, topic}, {sender, _call}, state) do

new_state =

Map.update(state, topic, [], fn subscribers ->

Enum.reject(subscribers, fn x -> x == sender end)

end)

{:reply, true, new_state}

end

@impl true

def handle_call({:subscribers, topic}, _sender, state) do

subscribers = Map.get(state, topic, [])

{:reply, subscribers, state}

end

@impl true

def handle_call({:broadcast, topic, message}, {sender, _call}, state) do

Map.get(state, topic, [])

|> Enum.each(fn subscriber ->

if subscriber != sender do

Process.send(subscriber, message, [])

end

end)

{:reply, true, state}

end

end

The subscribe and unsubscribe implementations use the call's sender to get the PID

to update the internal state.

When doing a broadcast, each subscriber is sent the same message using standard Process.send/3.

We exclude the sender, one of the possible semantics.

Let's see how this works in practice: in our three node cluster,

we subscribe each node to the same topic1 and broadcast a message from zed.

iex(zed@pathfinder)7> GenServer.start(PS, nil, name: {:global, :ps1})

{:ok, #PID<0.362.0>}

iex(zed@pathfinder)8> GenServer.call({:global, :ps1}, {:subscribe, :topic1})

true

The PID that subscribes is the one from IEX itself.

iex(foo@pathfinder)9> GenServer.call({:global, :ps1}, {:subscribe, :topic1})

true

iex(foo@pathfinder)10> self

#PID<0.110.0>

iex(foo@pathfinder)11> GenServer.call({:global, :ps1}, {:subscribers, :topic1})

[#PID<0.110.0>]

With three nodes subscribed, we can check out the list of subscribers. Note the node part of each PID.

iex(bar@pathfinder)8> GenServer.call({:global, :ps1}, {:subscribe, :topic1})

true

iex(bar@pathfinder)9> GenServer.call({:global, :ps1}, {:subscribers, :topic1})

[#PID<0.110.0>, #PID<13530.110.0>, #PID<14801.307.0>]

The node part of a PID is different on each node, i.e. each node uses a different remote identifier. Remember that PID's get translated when they transfer from node to node.

iex(foo@pathfinder)12> GenServer.call({:global, :ps1}, {:subscribers, :topic1})

[#PID<14487.110.0>, #PID<0.110.0>, #PID<14630.307.0>]

We can now broadcast a message from zed,

where we do not receive it ourselves since we explicitly exclude the sender.

iex(zed@pathfinder)9> GenServer.call({:global, :ps1}, {:broadcast, :topic1, {:msg, :yo}})

true

iex(zed@pathfinder)10> flush

:ok

On the other nodes we do receive the message as expected.

iex(foo@pathfinder)13> flush

{:msg, :yo}

:ok

iex(bar@pathfinder)10> flush

{:msg, :yo}

:ok

Our simple PubSub implementation is way too simple. One issue is the following: when a node dies, its PID is left stranded in the subscribers lists. On itself, that is no problem as sending a message to a non-existing or dead process is a no-op. But we can fix this, demonstrating yet another strong point about Distributed Elixir.

You probably know that one process can be linked to another process, in which case the dead of the second process will kill the first one, which we do not want here. The other option is for one process to monitor another process, in which case the monitoring process will receive a specific message when a monitored process dies.

This is the second, extended version of our code.

The subscribe call implementation is extended to call Process.monitor/1.

Finally we add an info implementation to deal with the DOWN message

and remove the PID from any subscribers list.

We do not have to differenciate between normal and abnormal exits.

defmodule PS do

use GenServer

@moduledoc """

A simple publish-subscribe server

"""

@impl true

def init(_) do

{:ok, %{}}

end

@impl true

def handle_call({:subscribe, topic}, {sender, _call}, state) do

new_state =

Map.update(state, topic, [sender], fn subscribers ->

if Enum.member?(subscribers, sender) do

subscribers

else

[sender | subscribers]

end

end)

Process.monitor(sender)

{:reply, true, new_state}

end

@impl true

def handle_call({:unsubscribe, topic}, {sender, _call}, state) do

new_state =

Map.update(state, topic, [], fn subscribers ->

Enum.reject(subscribers, fn x -> x == sender end)

end)

{:reply, true, new_state}

end

@impl true

def handle_call({:subscribers, topic}, _sender, state) do

subscribers = Map.get(state, topic, [])

{:reply, subscribers, state}

end

@impl true

def handle_call({:broadcast, topic, message}, {sender, _call}, state) do

Map.get(state, topic, [])

|> Enum.each(fn subscriber ->

if subscriber != sender do

Process.send(subscriber, message, [])

end

end)

{:reply, true, state}

end

@impl true

def handle_info({:DOWN, _ref, :process, process, reason}, state) do

IO.puts("DOWN #{inspect(process)} for reason #{inspect(reason)}")

new_state =

Map.new(state, fn {topic, subscribers} ->

{topic, Enum.reject(subscribers, fn subscriber -> subscriber == process end)}

end)

{:noreply, new_state}

end

end

Here is what we see on node zed when mini subscribes and then disappears.

iex(zed@pathfinder)12> Node.list

[:foo@pathfinder, :bar@pathfinder, :mini@enterprise]

iex(zed@pathfinder)13> GenServer.call({:global, :ps1}, {:subscribers, :topic1})

[#PID<27407.110.0>, #PID<26976.110.0>, #PID<26695.110.0>, #PID<0.307.0>]

DOWN #PID<27407.110.0> for reason :noconnection

iex(zed@pathfinder)14> GenServer.call({:global, :ps1}, {:subscribers, :topic1})

[#PID<26976.110.0>, #PID<26695.110.0>, #PID<0.307.0>]

iex(zed@pathfinder)15> Node.list

[:foo@pathfinder, :bar@pathfinder]

#PID<27407.110.0> got removed from the list of subscribers and mini left the cluster.

Again, how cool is it that process monitoring works across nodes of a cluster!

The source code for this and other experiments can be found in the distributed_elixir_exploration repository.

There is much more to learn about Distributed Elixir, here are some references to get you started:

It is also important to mention the Fallacies of distributed computing: communication between nodes in a cluster works so good it seems like magic, but it can fail. The good thing is, Elixir's philosophy is to always assume possible failures, even when doing local communication.